A 35 years old woman whose mother and sister died of ovarian cancer seeks your advice on her risk of developing the disease and how this can be reduced. How would you counsel her?

Ovarian cancer is the second most common gynaecological malignancy and the most common cause of gynaecological cancer death. The lifetime risk of ovarian cancer in the general population is 1.4%.

The strongest known risk factor for ovarian carcinoma is a family history, which is present in about 10 – 15% of women with ovarian cancer.

The risk of ovarian cancer is increased when the family history suggests a sporadic case but is substantially greater when there is a hereditary cancer syndrome. Women with (a single family member affected by epithelial ovarian cancer have a 4–5% risk) two affected relatives have a 7% risk of developing the disease. In contrast, women with hereditary ovarian cancer syndromes defined as having at least two first-degree relatives with epithelial ovarian cancer, have a lifetime probability as high as 13 – 50% for developing epithelial ovarian cancer.

It is important to differentiate those with a possible rare familial cancer syndrome and those with the more common presentation of an isolated family member with ovarian cancer, without evidence of a hereditary pattern.

This can be achieved with the clinical notes of the mother and sister regarding age of onset, histological type, grade, concurrent breast / fallopian /peritoneal/endometrial/colon cancer and gene mutation study.

Women with a family history but without evidence of a hereditary pattern (low risk family history) should be counselled about their individual risk – considering age, parity and history of oral contraceptive pill use.

Women with a suspected hereditary ovarian cancer syndrome (high risk ) should be referred to a genetic counsellor for consideration of testing for BRCA mutations or HNPCC if suspicious with the family history.

BRCA mutations may account for up to 90% of hereditary ovarian cancers. HNPCC carriers account for 1% of ovarian cancers. The estimated risk of ovarian cancer is 35–46% for BRCA1 mutation carriers and 13–23% for BRCA2 mutation carriers. Lynch syndrome have a 3–14% lifetime risk of ovarian cancer.

The stage at presentation of ovarian cancer is similar for BRCA carriers and the general population – approximately 70% of patients present with stage III/IV disease. Ovarian cancers in BRCA mutation carriers are more likely to be of higher grade than ovarian cancers in age-matched controls. However, BRCA mutation carriers, particularly BRCA2 carriers, have a better prognosis than non-carriers.

There is no evidence to support screening in low risk group and decisions regarding screening and risk-reducing surgery should be based on individualised considerations involving the patient and clinician.

Screening has not been associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality from ovarian cancer. As interval cancers can develop between screening visits and are often advanced at presentation & serum CA125 levels are only elevated in 50–60% of stage I ovarian cancers. It is not appropriate to use screening to reassure high-risk women and it should only be offered in women declining risk-reducing surgery, in the absence of a better alternative.

Screening with transvaginal ultrasound plus CA125 assays every 6 months, starting at the age of 35 years or 5–10 years earlier than the earliest age of first diagnosis of ovarian cancer in the family.

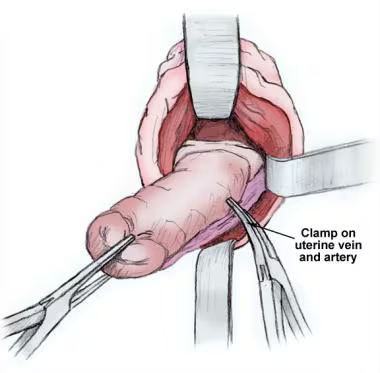

Lack of efficacy of ovarian cancer screening has prompted to recommend risk-reducing laproscopic bilateral salpingooophorectomy (rrBSO). The reason for BSO rather than oophorectomy alone is theory explain BRCA-associated pelvic serous carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube, from a lesion called serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), and subsequently spread to the ovary and peritoneum.

Pelvic ultrasound and CA125 level to evaluate for the presence of an ovarian malignancy should therefore be performed prior to surgery.

Of women with a BRCA1 mutation and ovarian cancer is diagnosed before the age of 50 years in 54%. Diagnosis before the age of 40 is uncommon (2–3%) and under the age of 30 is rare. It is appropriate to consider rrBSO for BRCA1 carriers after the age of 35 once childbearing is completed.

BRCA2 carriers reach a 2–3% incidence a decade later, by age 50 years and the average age at diagnosis is 60 years – similar to the general population. Based on this difference in the likely age of onset of ovarian cancer, BRCA2 carriers may wish to delay their risk-reducing surgery but by doing this they would not benefit from the reduction in breast cancer afforded by salpingo-oophorectomy.

BSO in premenopausal women with BRCA mutations has the additional benefit of significantly reducing the risk of breast cancer by 30 to 75%. Risk-reducing breast surgery or breast screening depend on the woman’s decision.Relative risk of ovarian/fallopian tube/peritoneal cancer after rrBSO was 0.04% – 0.25% varies.It is important to remember that rrBSO is not completely protective and BRCA carriers still have a risk of developing primary peritoneal cancer (approximately 2% risk)

Removal of healthy ovaries does not add significantly to the operating time or immediate surgical complications of hysterectomy, but may have significant implications for short- and long-term health.

If RRBSO is undertaken premenopausally it will leads to premature menopause. Surgical menopause differs from natural menopause in that hormone levels drop abruptly and hormone production ceases completely, as opposed to a gradual decline in hormone level and continued production of androgens as occurs with natural menopause. Those exposed to the detrimental effects of hypoestrogenism such as hot flushes, sleep disturbance, mood change and hair and skin changes. Sexual-health-related effects include dyspareunia secondary to vaginal atrophy and decreased libido. Long-term health effects include osteoporosis, cardiovascular disease and effects on cognitive and psychological function.

If RRBSO is undertaken premenopausally, BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers who do not have a personal history of breast cancer should be offered hormone replacement therapy (HRT) at least until the age of natural menopause, around 50 years, in order to abrogate the cardiovascular and bone complications. For women with a history of breast cancer, the use of HRT is not usually recommended. Factors that could possibly lower the potential increased risk of breast cancer with HRT use include limiting the duration of use until the age of 51 (the average age of natural menopause), concurrent hysterectomy to enable the use of unopposed estrogen and prophylactic mastectomy.

Women who undergo rrBSO are at increased risk of osteoporosis and should be counselled about osteoporosis prevention, treatment and screening.

Vaginal atrophy can be treated with vaginal estrogen preparations. Low-dose vaginal estrogens typically do not raise the serum estrogen concentration above natural menopausal levels. Non-hormonal preparations can be used as first line treatment but if these prove inadequate, vaginal estrogen is a reasonable option. Use of vaginal estrogen in women with a history of breast cancer has not shown an increase in recurrence rates but data are limited.

Hysterectomy may be performed at the same time as BSO when there are other gynaecological indications, Lynch syndrome who are at increased risk of endometrial cancer, some BRCA carriers wish to take tamoxifen (increased risk of endometrial pathology) for chemoprophylaxis of breast cancer, women who wish to take unopposed estrogen therapy may consider concurrent hysterectomy.

Women considering rrBSO with fertility wish should be counselled about alternative reproductive options including embryo cryopreservation. Surrogacy is an option for those undergoing concurrent hysterectomy.

Radical fimbriectomy consists of removing all of the fallopian tube and the fimbrio-ovarian junction. This option for women who wish to retain their ovarian function and fertility in preference to having no prophylactic surgery at all. The safety and effectiveness of radical fibriectomy for reducing ovarian carcinoma in the BRCA population has not been assessed in clinical trials.

Women with a hereditary ovarian cancer syndrome who have not elected for risk-reducing surgery and who are not trying to conceive should consider COCP use. COCP was associated with significantly reduced risk of ovarian cancer. The protective effect increased with longer duration of use. RR decreased by about 20% for each 5 years of use; by 15 years the risk of ovarian cancer was halved. Importantly, the protective effect persisted for 30 years after cessation of OCP use although the effect attenuated over time.

Studies have not shown a significantly increased risk of breast cancer in users overall, or in the first 10 years after cessation of use of recent oral contraceptive formulations.